Often the Middle Ages are distilled to a handful of elements—castles, feudalism, monarchy, religion, and folklore. But as with any historical period, dominant perspectives and popular culture shape how we view, understand, and engage with the past. The Middle Ages is no different, but we must take this into further consideration when seeking to find the place of queerness in medieval history. Contemporary discussions and studies of LGBTQ+ history are increasingly looking further back into the past to trace the great arch of queerness across human history, beyond recent decades and centuries.

However, in approaching queer identity and LGBTQ+ figures in medieval European history, we must be cautious of our contemporary terminology and understandings, for much of what we use to define queerness today does not cleanly apply to the past, especially the medieval period. While this survey will be brief, it will nonetheless be evident that queerness and external understandings of it differ in many ways from those in our own time, yet there are many things that remain consistent or overlap.

In exploring queer medieval European history with regard to its contemporary academic approach, religious understanding within the bounds of sodomy, expressions in monastic communities, and presence in the era’s literature, we are able to draw parallels between queer medieval history and contemporary queer history—particularly in how religion influences and exhibits queerness, how queerness is present in popular culture, and how queerness is understood based on different cultures and time periods.

Studying Queer Medieval History

The academic area of study that is queer medieval history is relatively recent and relatively niche; it finds its roots in the queer liberation movement and its influence on scholarship along with the mere lack of academics focusing on this particular subject.

There are indeed a limited number of resources on queerness in the Middle Ages; as V. A. Kolve writes in their article “Ganymede/Son of Getron: Medieval Monasticism and the Drama of Same-Sex Desire,” they primary hurdle to researching queer people in this period is “simply lack of data” (Kolve 1998, 1014). Kolve expounds upon this point, stating that the erasure of queer people from history and lack of queer scholarship can be attributed to homophobia in academia, and unfortunate reality that only reflects homophobia’s continuing prevalence in every sphere of life (Kolve 1998, 1014). However, this does not mean that queerness is never mentioned, present, or inferred through historical accounts and other textual works.

It is crucial to understand that our contemporary terms of homosexual, gay, and queer must be applied to the Middle Ages—along with other historical periods prior to the 19th century—with caution, as our understandings and applications of these terms were not present back then or understood in different ways (Kolve 1998, 1015). Rather than flippantly impose our understandings of queerness onto the Middle Ages, we must use the aforementioned terms and their contemporary understandings with caution as we allow ourselves to be informed by—and sensitive to—the ideologies, theologies, popular works, and tendencies of the past. If there is one thing we must avoid, it is wrongful imposition which leads to distortion, bastardization, and misrepresentation.

We must use the [homosexual, gay, and queer] and their contemporary understandings with caution as we allow ourselves to be informed by—and sensitive to—the ideologies, theologies, popular works, and tendencies of the past.

In his paper “Becoming (Queer) Medieval: Queer Methodologies in Medieval Studies: Where Are We Now?” Michael O’Rourke notes that the intersection of queer and Medieval studies “has often been as productive as it has been hostile,” with many in both fields being suspicious of the other or reluctant to engage (O’Rourke 9). Stephen Morris expounds on O’Rourke’s point in his paper “Are We Queer? Are We Medieval? The Need to Be All Things to All People,” stating that both of these fields of study have fallen prey to ghettoization, calling them to “reach out” and “broaden their scope” (Morris 25). It is clear to us that queer medieval history is a field which is very much still in its infancy, yet there is much that has already been uncovered, deciphered, analyzed, and discussed.

While queer medieval history is but a small subset of queer history and of the contemporary field of queer studies, its struggles and goals reflect those of other queer scholars and the trends in LGBTQ+ academia—the desire to shed light on histories once hidden or erased while combating external forces which seek to quell its progress based on homophobic intentions. Queer identity as a whole is marked by struggle, the fight for inclusion, the hope for affirmation, the desire for representation, and the need for justice. In their own way, scholars in the field of queer medieval history are striving to both reclaim and proclaim—reclaim expressions of queerness that were condemned in the past and proclaim the undeniable presence of queerness in human history.

Religion & Defining “Sodomy”

Christianity was the social, cultural, and religious cornerstone of medieval Europe, with the faith— in its institutional and popular manifestations—permeating all spheres of life, both public and private. Medieval Christianity did not use the terms homosexual, gay, or queer to refer to individuals whose sexuality and gender were not normative, nor did they ever identify what we now understand as queerness to any particular identity. Rather, gender and especially sexual non-normativity was placed under the umbrella term of sodomy. While terms such as homosexual, gay, or queer attempt to identify a particular identity, sodomy is a term used to define a category of carnal transgressors—individuals who have exercised sexual impropriety.

Derived from the biblical narrative of Sodom and Gomorrah which many have historically interpreted as being centered around sexual deviance and moral degeneracy, the medieval Christian understanding of sodomy identifies it with acts such as same-sex intercourse, bestiality, masturbation, and sex outside of marriage and the intention of procreation (Kolve 1998, 1016). Sodomy did not exclusively pertain to same-sex relations, but to anything sexual that was non-normative. Moreover, sodomy was not tied to a particular identity, or what we would now refer to as sexuality, but to particular acts, meaning that any person was capable of being a sodomite. Fabian Alfie writes in his paper “Sinful Wives and Queens: The Medieval Concept of Sodomy in Dante’s Comedy” that sodomy in medieval Christianity was, in essence, a “sexual sin,” an outright transgression against Natural and Divine Law, with numerous theologians throughout early Christianity identifying same-sex relations, among other things, as such (Alfie 2002, 107).

Theological works, confessional manuals, and sermons are examples of textual forms that have been recovered and analyzed by scholars which have provided further evidence of discussion regarding sodomy in medieval Christianity (Alfie 2002, 107). One of these authors was the Benedictine monk Peter Damian; in his article “Queer Medieval: Uncovering the Past,” Graham Drake writes that the prevailing understanding of sodomy has its roots in Damian’s work Liber Gomorrhianus—the Book of Gomorrah—written in the eleventh century, in which he argues that sodomy, in all of its manifestations, is unnatural and abhorrent to God (Drake 2008, 639). A century after Damian, the Dominican priest and theologian Thomas Aquinas expounded on his teachings on this subject, stating that normative sexual activity was grounded in procreation, with anything that diverged from it to be considered sodomy and the persons involved to be identified as sexual deviants who have offended both God and nature (Alfie 2002, 108). It is seemed from these theological understandings of sodomy that emphasis was placed on sex and sexuality rather than gender. However, this does not mean that gender non-normativity was not present in medieval Europe; in later sections, queer expressions of sexuality and gender were present in other realms of medieval Europe.

In reflecting on the religious roots of medieval Europe’s understanding of queerness, we see how religion plays a significant role in defining and addressing queerness. We have seen the same patterns here in the United States where religious conservatives and liberals have played pivotal roles in the evolving landscape of LGBTQ+ life in this nation. Both sides and everything in between are informed by scripture, tradition, reason, and culture just as those in medieval Europe. In particular, the positions of theological conservatives in medieval Europe such as Damian and Aquinas parallel those of figures such as Jerry Falwell and Pat Robertson of the Moral majority movement in the United States during the 1980s. Both Falwell and Robertson utilized religion to influence politics in order to gain more ground in American culture, and made the same arguments Damian and Aquinas made, namely that homosexuality was a sin as it is unnatural and a transgression against both Divine and Natural Law. Medieval theological understandings of homosexuality and sodomy as a whole similarly influenced laws, decrees, and cultural norms during the period.

Medieval Monasticism & Queerness

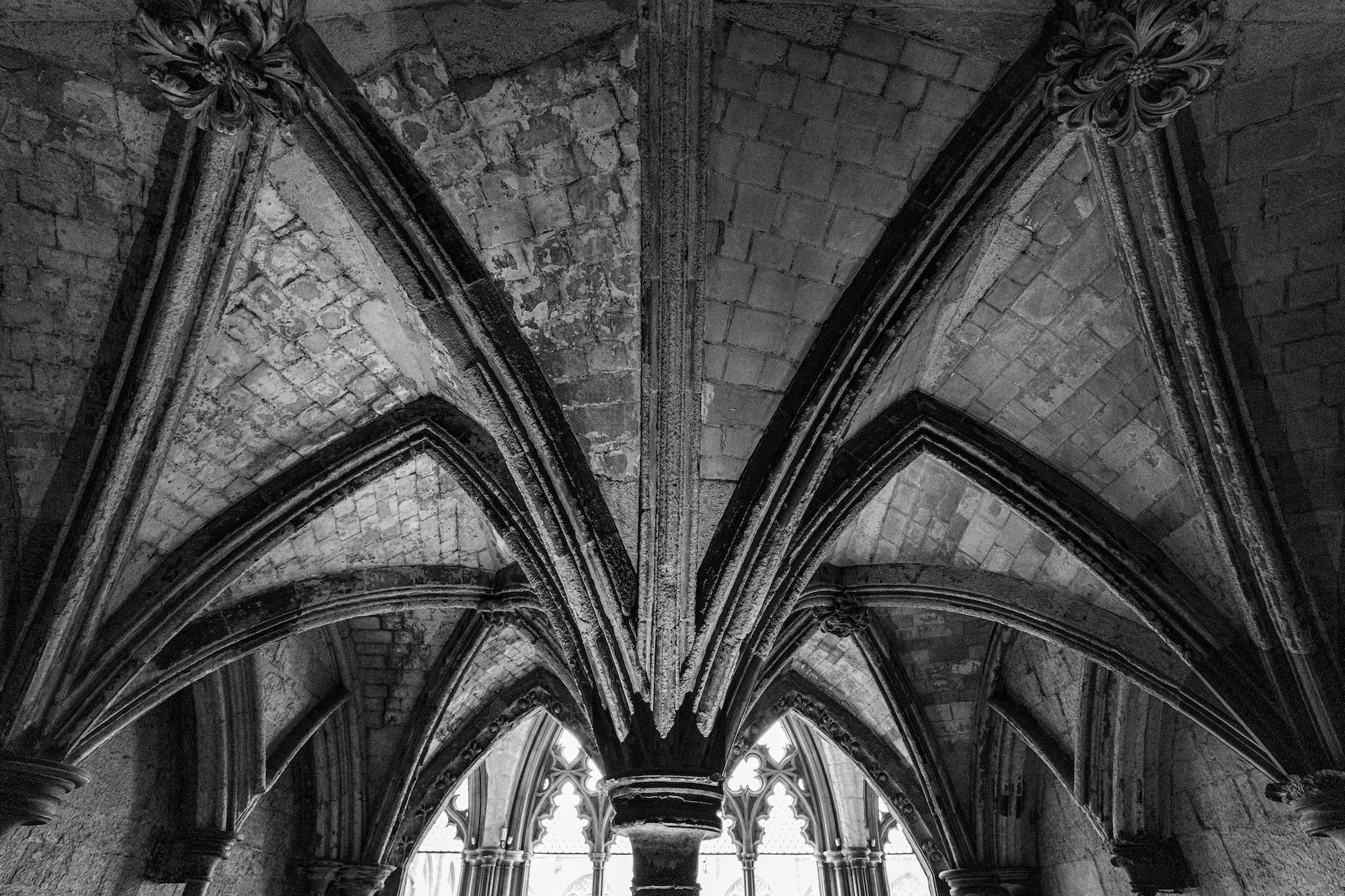

Monasticism in medieval Europe was a cornerstone of religion, scholarship, and politics. Within the cloisters of monastic institutions dwelled individuals who sought to dedicate their lives to God through living out the vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience. To a great degree, monastics—both monks and nuns—lived truly cloistered lives, sparsely engaging with the secular world beyond the monastery’s walls. With such seclusion comes the inevitability of encounter and the possibility of intimacy among those within.

While many people tend to favor readings of medieval monasticism that lean toward homoerotic relationships existing under the suspicious gaze of the particular order’s rule and within the shadows of the cloisters, some academics such as Christopher Jones dismiss these claims as mere digressions driven by the human interest in drama and the irresistibility of a good scandal. In his paper “Monastic Identity and Sodomitic Danger in the ‘Occupatio’ by Odo of Cluny,” Jones writes that monasteries “offered few opportunities for heterosexual fornication” especially in those where observances of their rule—or holistic code of conduct—were strictly enforced, allowing little room for such relationships to develop, let alone last, if they were likely both to be overtly opposed and quickly caught (Jones 2007, 26). As for the propensity for contemporary folks to want to believe narratives that frame monasteries as hotbeds of queer activity, Jones states that there was, at least, a reasonable likelihood that queer activity was at the very least likely and never impossible, stating that the monastic environment would have fostered “at least a ‘situational’ or ‘opportunistic homosexuality’” (Jones 2007, 26).

Relatedly, he states that homoeroticism in monasteries has been both implied and evidenced in the writings, from abbey records to fictional works, with monastic sources being particularly crucial as they give a seemingly first-hand account of such instances; Jones posits that the homoeroticism present in these texts has sometimes been wrongfully identified by some scholars as merely “spiritual friendships” (Jones 2007, 1). He also notes the irony—and tinge of hypocrisy—of medieval monasticism’s adamant condemnation of homosexuality, stating that “institutions that liberally recuperated the homoerotic could simultaneously play an aggressive role in demonizing ‘sodomy,’ having the opposite effect of their initial intentions (Jones 2007, 2). He posits that queer interactions and relationships in medieval monasteries ranges from “homosexual” to “homosocial,” with non-normative behavior manifesting in ways such as the upending of traditional gender expressions or engaging in same-sex intercourse (Jones 2007, 40).

While Jones speaks broadly about monastics, both men and women, Drake narrows his focus on nuns and cloistered women—female monastics. In particular, he further narrows his focus on the figure of Héloïse, a French nun, abbess, and writer who lived during the medieval period known most notably for her letters; he notes that her convent was suspected by numerous external figures at the time to harbor some homosexual activity (Drake 2008, 650). In Drake’s view, the monastic vows of chastity along with the expectation for unmarried women to remain virgins could foster “a new kind of desire” within these female monastic communities he terms as a “queer space” (Drake 2008, 650).

By looking into the presence of queerness in medieval monastic communities, we see how queer individuals expressed their identities in particular contexts, whether it is in existing institutions which they happen to be associated with or organizations deliberately created in order to foster encounters among queer people. In the case of these monastic communities, expressions of queerness were moreso accidental than intentional, but it must be understood that queer people are present in all spheres of life.

Queerness In Medieval Literature

Queerness, as with any other identity, can be found in literature, for part of literature’s purpose is to express and reflect the human condition. While queer writers from the medieval era are difficult to identify, there have been numerous queer literary characters that scholars have identified through a distinctly queer reading of such texts. Richard Zeikowitz, in his paper “Befriending the Medieval Queer: A Pedagogy for Literature Classes,” provides examples of three queer characters in medieval literature: Grendel from Beowulf, the Green Knight from Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, and the Pardoner from The Canterbury Tales (Zeikowitz 2002, 67). He briefly explains his identification of these three male figures as queer, positing that their self-concepts, identity, characteristics, and activity “pose a challenge or threat to normative homosocial desire” as it was generally understood in medieval Europe (Zeikowitz 2002, 67). By their textual sources alone, we can see that queer characters exist not only in medieval era texts, but prominent texts from this period which remain beloved and passionately studied

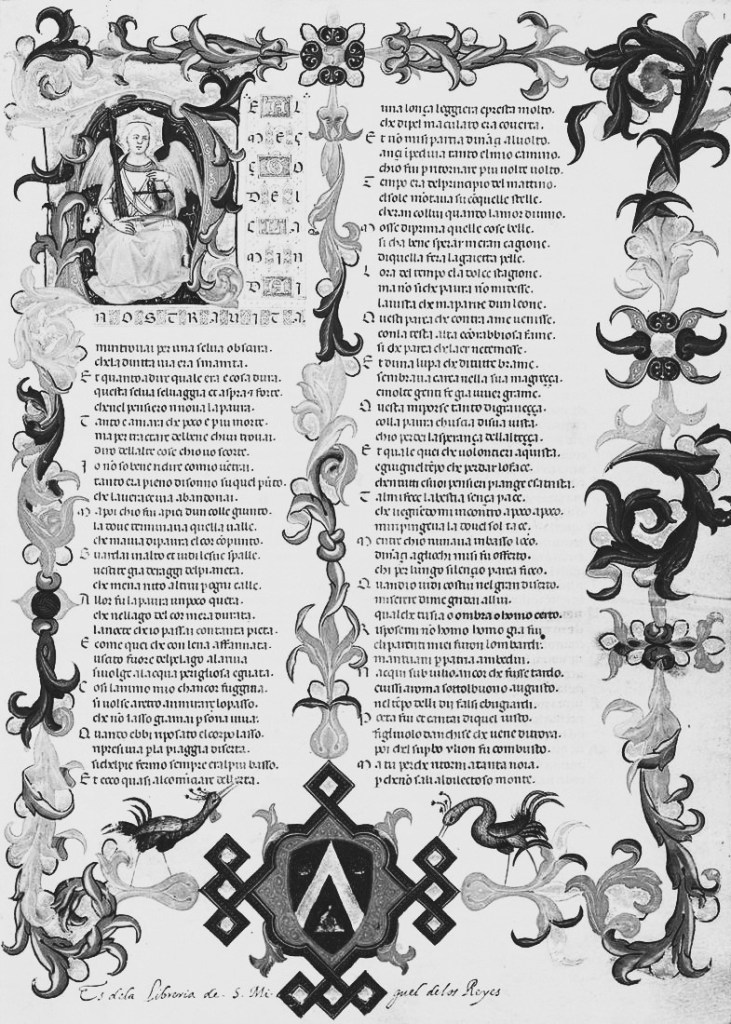

A page from an illuminated manuscript edition of Dante’s Divine Comedy, illustrated by Italian monastic and illuminator Don Simone Camaldolese.

Image by JarektUploadBot on Wikimedia Commons

Returning to the subject of sodomy, we see it addressed both religiously and literarily in Dante’s Divine Comedy. Afie draws us into this work by stating that its author “dealt with ‘sodomites’ twice in his masterpiece, once in Inferno and again in Purgatorio” (Alfie 2022, 101). As was clarified earlier, sodomy as understood in Christian theology and broad European culture during the medieval period was not exclusively tied to homosexuality but to numerous sexual acts that were deemed illicit, unnatural, and immoral. Dante’s work reflects this understanding, with Alfie noting that “some of whom might not have bedded other men.

Examination of the passage in Purgatorio, moreover, indicates a greater degree of subtlety in Dante’s thought regarding non-normative sexual attraction, with some of the offenders having been identified as having had homosexual intercourse while many others had exhibited other sodomistic behavior (Alfie 2022, 101). Furthermore, Alfie observes that Dante’s understanding of “human depravity” both included and went beyond sodomy, showing that his portrayal of moral transgressions—especially those of a sexual nature—was far more nuanced than one may assume (Alfie 2022, 103). This understanding of sodomy as an umbrella-term coupled with Dante’s authorial intentions in his Divine Comedy signal to us once more that the medieval understanding of queerness and homosexuality was one relating to sexual activity—rather than sexual identity—within the bounds of its particular understanding of sodomy.

As we reflect on the presence of queer figures in medieval literature, we can draw parallels to the emergence and development of pulp fiction and the censoring of films containing queer characters in the United States.

Past, Present, & Future

Having briefly explored some facets of queer medieval history, we are now posed with the question: “So what?” In other words, we are faced with the question of meaning and significance. When considered in the overarching spectrum of LGBTQ+ history, queer medieval history finds its significance in the very disruption queer individuals brought to the social, religious, and cultural aspects of medieval Europe—reflecting the pattern present throughout history of queer people being outliers but every present in ways both explicit, implicit, and broadly hidden.

Through the presence of queer people in medieval texts, literary works, theologies, and religious institutions parallels to queer identity today and the challenges that many queer people throughout the world continue to face—from combating bigotry to the desire for representation.

Through the presence of queer people in medieval texts, literary works, theologies, and religious institutions parallels to queer identity today and the challenges that many queer people throughout the world continue to face—from combating bigotry to the desire for representation.

The struggle we face in studying queer medieval history is that much of the period’s discussion on queerness is primarily focused on homosexual or same-sex intercourse, which is but the tip of the iceberg with regard to sexuality let alone queer identity as a whole. In her paper “The Normal, the Queer, and the Middle Ages,” Amy Hollywood cites fellow academic Carolyn Dinshaw who states that queerness is not something clear and concrete; rather, it is “a relation to a norm, and both the norm and the particular queer lack of fit will vary according to specific instances” (Hollywood 2001, 173). Hollywood expands on this, stating that the “presumed distinction between acts and identity” was different in the Middle Ages when compared to the nineteenth century’s emergence of the medical model of homosexuality and our twenty-first century understanding (Hollywood 2001, 174).

In many ways, queer medieval history represents continuity, specifically in how expressions of queerness can be found in popular culture—specifically literary works, and how understandings of queerness are heavily influenced by religion. However, it also represents change, a shift in the understanding of queerness, encompassing both gender and sexuality, through a legalistic and theological approach which sought to identify same-sex relations and non-conforming expressions of gender as immoral and unnatural. Its long-term effects can still be found today in the prevalence of religious views held by some which adhere to the same anti-LGBTQ stances derived from particular understandings of Divine and Natural Law.

Yet in my mind, the many gray-areas and unexplored regions of queerness in medieval European history is the most resonant aspect of this subject. Zeikowitz cites writer and academic Carolyn Dinshaw who states that “[q]ueerness works by contiguity and displacement, knocking signifiers loose, ungrounding bodies, making them strange” (Zeikowitz 2002, 70). The medieval European understanding of queerness’s strangeness is in its incongruence. However, this understanding limits queerness to sexuality rather than gender. Further exploration of queerness in medieval history should address figures such as Joan of Arc who bent gender norms and in her own way ungrounded bodies—namely her own.

In looking back, we must simultaneously look to the present, recognizing that there are elements which distinguish our contemporary understanding and expressions of queerness from the past’s, preventing us from incorrect assumptions and harmful projection which foster healthy comparison and concrete distinctions. There is much left to uncover about queer history through every period, culture, and facet of life. Our inquisitiveness and affirmation of queer identity must further galvanize us to explore our queerness in its fullness across time as space, which ultimately reminds us that we have, will, and always be present in all our complexity, diversity, and queerness.

Author’s Note: This blog post was written as my final project for the course LGBTQ+ History in the United States at San Jose State University. I acknowledge that there are many unspoken things and untouched subjects in the blog post; this was meant to be a general survey of queer medieval history, focusing on primary things such as culture, religion, politics, and contemporary academic approaches to the subject.

Sources:

Alfie, Fabian. 2022. “Sinful Wives and Queens: The Medieval Concept of Sodomy in Dante’s Comedy.” Journal of Language & Sexuality 11 (1): 101–24. doi:10.1075/jls.19010.alf.

Drake, Graham N. “Queer Medieval: Uncovering the Past.” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 14, no. 4 (2008): 639-658. muse.jhu.edu/article/251045.

Hollywood, Amy. 2001. “The Normal, the Queer, and the Middle Ages.” Journal of the History of Sexuality 10 (2): 173. doi:10.1353/sex.2001.0030.

Jones, Christopher A. “Monastic Identity and Sodomitic Danger in the ‘Occupatio’ by Odo of Cluny.” Speculum 82, no. 1 (2007): 1–53. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20464015.

Kolve, V. A. “Ganymede/Son of Getron: Medieval Monasticism and the Drama of Same-Sex Desire.” Speculum 73, no. 4 (1998): 1014–67. doi.org/10.2307/2887367.

Morris, Stephen. “Are We Queer? Are We Medieval? The Need to Be All Things to All People.” Medieval feminist forum 36 (2003): 25–30.

O’Rourke, Michael. “Becoming (Queer) Medieval: Queer Methodologies in Medieval Studies: Where Are We Now?” Medieval feminist forum 36 (2003): 9–14.

Zeikowitz, Richard E. “Befriending the Medieval Queer: A Pedagogy for Literature Classes.” College English 65, no. 1 (2002): 67–80. doi.org/10.2307/3250731.

Leave a comment